The Strategy That Could Help US Decouple From China’s Rare Earths

The United States and its allies are weighing the rapid reopening of long-abandoned mines to rebuild secure supply chains.

Don’t miss my extensive interview on America’s Rare Earths strategy and how you can profit from it on “Economic War Room with Kevin Freeman”.

This analysis is free, but with Premium Membership you get MORE. Join today.

by Owen Evans

December 11, 2025

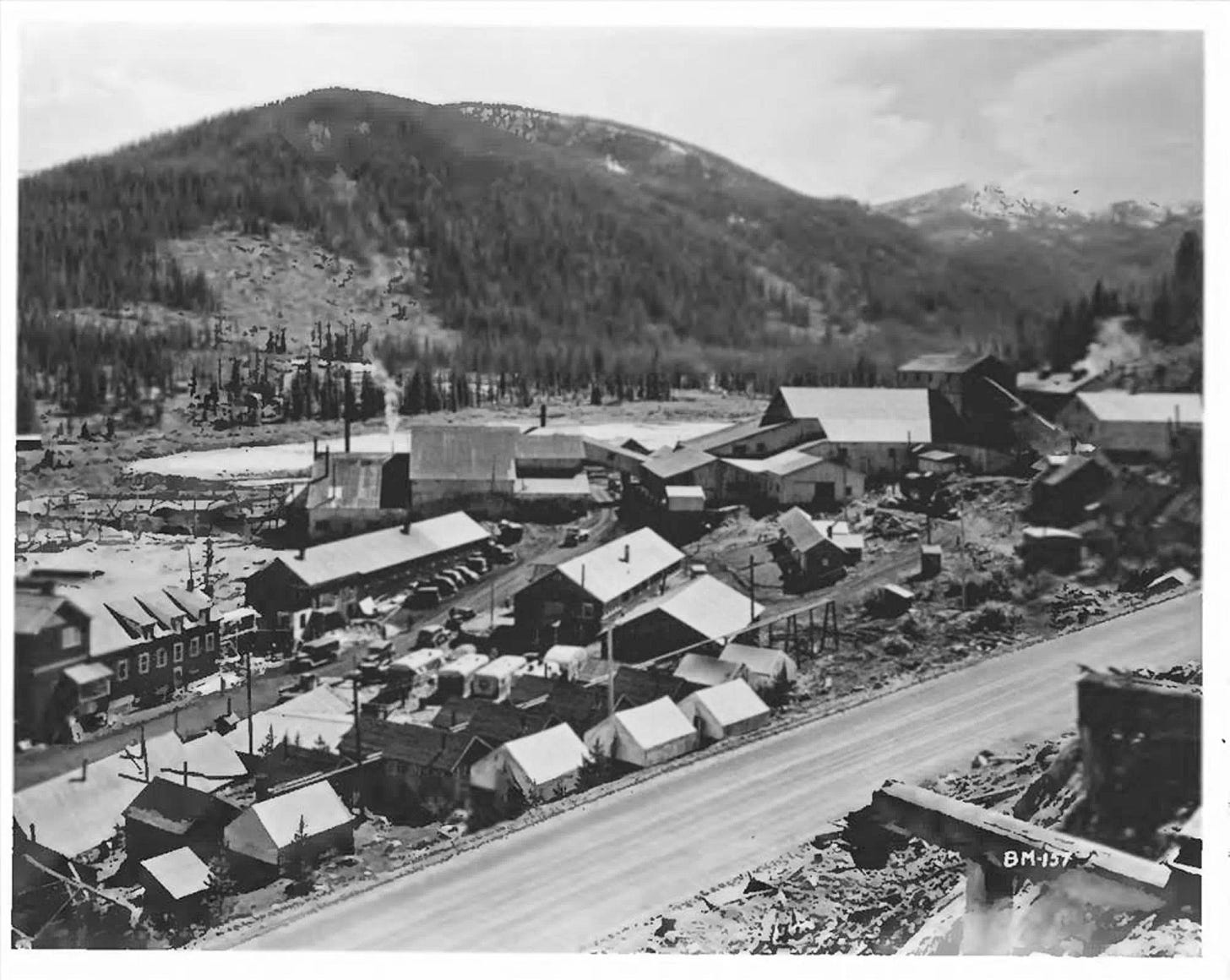

Boarded-up mines across the world are rusting symbols of how China seized the world’s critical minerals supply chain. Now, some of these mines — closed not because they ran dry, but because of Beijing’s oversupply and price dumping — could be reopened as the Trump administration rallies nations to overthrow China’s supply chain dominance.

Getting a new mine up and running can take up to 15 years. Mothballed mines could provide a timely stopgap. Still, digging out the minerals is only half the challenge. When the United States and the broader Western world abandoned their mines, they also abandoned the race for the all-important extraction process.

Arizona-based mining automation consultant Avadh Nagaralawala said reopening mines is “a tempting shortcut.”

“The ore bodies are proven, some infrastructure remains, and timelines can be shorter than starting from scratch,” Nagaralawala said. Such projects also “carry powerful symbolism”.

Even so, Nagaralawala noted that many sites had been closed because of declining grades, high operating costs, and local resistance to pollution. “The hard truth remains: The West wants more minerals but fewer mines in its own backyard,” he said.

Rare-earth elements, a group of 17 metals crucial to everything from permanent magnets in wind turbines to electric vehicle motors, are hard to extract and even tougher to process. Much of the essential refining technology and know-how now lies in China’s hands, along with the all-important supply chains.

The same pressures apply to other critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and copper, which underpin battery production and much of the modern electricity system.

Over the past few months, the trade war between the United States and China brought the issue of Beijing’s control of critical minerals to a head. In October, the Trump administration announced critical mineral deals worth more than $10 billion with Australia, Cambodia, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand to strengthen allied supply chains.

President Trump also recently said the United States would end its reliance on China for rare-earth minerals within 18 months under an “emergency program.”

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said in Nov. 1 that China had “made a real mistake” by threatening to curb exports, which spurred the United States and its allies to fast-track new sources.

On Nov. 6, the administration added 10 minerals, including copper and metallurgical coal, to its list of materials vital to national security.

Brussels is not sitting idly by, either. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on Oct. 25 that the bloc will unveil a new plan by year-end to diversify Europe’s mineral supply away from China.

The challenge is vast. The world needs about 300 new mines over the next 25 years just to meet current demand, according to Troy Hey, executive general manager at global miner MMG, which is majority-owned by China Minmetals.

“You know how hard it is to get one mine up, let alone 300,” Hey said at a business conference on Oct. 28, according to Australia’s News.com.au. He said the required infrastructure, investment, and skills would be “an order of magnitude beyond” what the industry has seen in the past two decades.

Dormant or Suspended Projects

Across the United States, Australia, Canada, and Europe, dozens of long-dormant or suspended mining projects are now slated to reopen or are under active review. These projects include sites where companies are conducting feasibility studies, securing permits, or arranging financing to restart production.

In the United States, for example, Idaho’s Stibnite Mine, once a key source of antimony during World War II, is now being redeveloped with government backing.

The United States also still maintains a major foothold with the Mountain Pass Mine in California, the only fully integrated rare-earth mining and processing site in North America, which by 2022 supplied about 15 percent of global output.

Operations at Jervois Global’s Idaho cobalt mine, the only primary cobalt mine in the United States, have been suspended because of Chinese-controlled supply chains in the Democratic Republic of the Congo driving prices below viability.

In Australia, the historic Mount Morgan Mine, which has been closed since 1981, is now undergoing rehabilitation and is slated for reopening. New investment was announced in 2025 to restore production at one of the country’s oldest gold sites.

In Australia’s Northern Territory, the Nolans Rare Earths Project is under construction, combining a mine, processing plant, and separation facility.

In 2024, BHP Group suspended its Western Australia nickel operations, citing a price collapse triggered by Chinese-dominated oversupply from Indonesia. Yet it still exists.

In Sweden, the Woxna graphite mine remains on standby, but would require major investment to restart. Graphite is the largest raw material component in electric vehicle batteries, and China currently refines nearly all of the world’s battery-grade supply.

In the UK, the Hemerdon (Drakelands) tungsten and tin mine in Devon, which holds the world’s fourth-largest tungsten resource, was suspended in 2018, but plans to restart are underway.

And in Ireland and southern Europe, several sites, including Ireland’s Navan (Tara) zinc-lead mine and Spain’s Barruecopardo tungsten mine, are being reviewed or restarted.

Understanding Reopening

Reopening old mines has its limits, said veteran geologist Darren Bahrey, founder, president, and CEO at StrategX Elements Corp., who has more than 30 years of experience in mining development.

“Opening old mines makes sense where there’s clear economic potential or cleanup value, but the real contribution will come from new exploration in regions that can fast-track development into the supply chain,” Bahrey said.

He noted that Canada is a “standout example,” following the federal government’s recent $2 billion investment. “New mine development and processing capacity will be essential, and governments need to make permitting a priority rather than a bottleneck.”

“The real shortage lies in our basket of critical minerals (nickel, vanadium, copper, cobalt, and graphite).”

Bahrey said there is “definitely rising demand” and that the region to watch is the Americas.

There is also an environmental case for reopening mines, which, once abandoned, can discharge increasing amounts of pollutants into rivers and aquifers over time. “Water can accumulate and turn acidic, tailings can oxidize, and infrastructure like liners or containment systems can fail over time without maintenance,” Bahrey said.

“Limited, well-managed operations often reintroduce active water treatment, monitoring, and containment, which can make the overall footprint cleaner and more sustainable over time than leaving the site to deteriorate unmanaged.”

Mining Alone Will Not Thwart China

Steve Christensen, cofounder and chief executive of the Responsible Battery Coalition, said that the mining industry is grateful for Trump’s leadership so far. But he said mining more material does not solve the issues of China’s market manipulation.

“They’ll dump their cheap materials into a market, they’ll lower the price so far down, they’ll take a loss on it,” he said.

“When your competitor doesn’t care about profits, it’s very hard to compete.”

Bob Bilbruck, founder and CEO of the strategic consulting firm Captjur and an expert in the mining sector, says that the Biden administration, through the Environmental Protection Agency, “made it almost impossible to expand mining at these existing or mothballed mines.”

He said the Trump administration should “federalize these mines and open and enlarge production and processing.”

The Value in Waste

Much of the metal that could ease shortages is trapped in low-grade ore, tailings, and waste rock, beyond the reach of current extraction techniques.

Scientist and inventor Eric Herrera is CEO of MaverickX, a company that is developing methods to recover more metal from existing ore and waste. The invention of the extraction technology was driven by the collapse of lithium prices.

“Now we’re starting with uranium, radium, and rare-earth elements as well,” he said.

All kinds of metals are mixed together in various states within mineral rocks, according to him.

He said his approach is to “take everything out.”

“Let’s juice that rock for all it’s worth — that’s basically what we’re doing,” Herrera said.

He said recovering rare earths from discarded electronics and other industrial waste is one of the lowest-hanging fruits.

He also pointed to gallium, used in semiconductor applications such as integrated circuits and LEDS, as proof of concept. There are no gallium mines; gallium is a byproduct of processing other ores, a process China perfected and now controls 80 percent of globally.

“Emulating that process is going to be absolutely essential,” Herrera said.

“The problem there is that technology — the gallium technology, the rare earth and separation technology — all developed in the United States. It was abandoned.”

— This essay is published in cooperation with The Epoch Times.

Really insightful piece. The mothballed mines angle is interesting but Christensen's point about China's price dumping probaly cuts deepest here. Opening up Mountain Pass or Stibnite is only half the battle when Beijing can just flood the market with below-cost material and make the wohle thing economically unviable again. The processing tech gap is where this really gets tricky since that knowhow was straight-up abandoned decades ago.