The New China-U.S. Nuclear Arms Race

The New START Treaty has expired, & the last limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons are gone. But China has never submitted to any limit. And now it's building up, fast.

by Rod D. Martin and Melissa Lawford

February 12, 2026

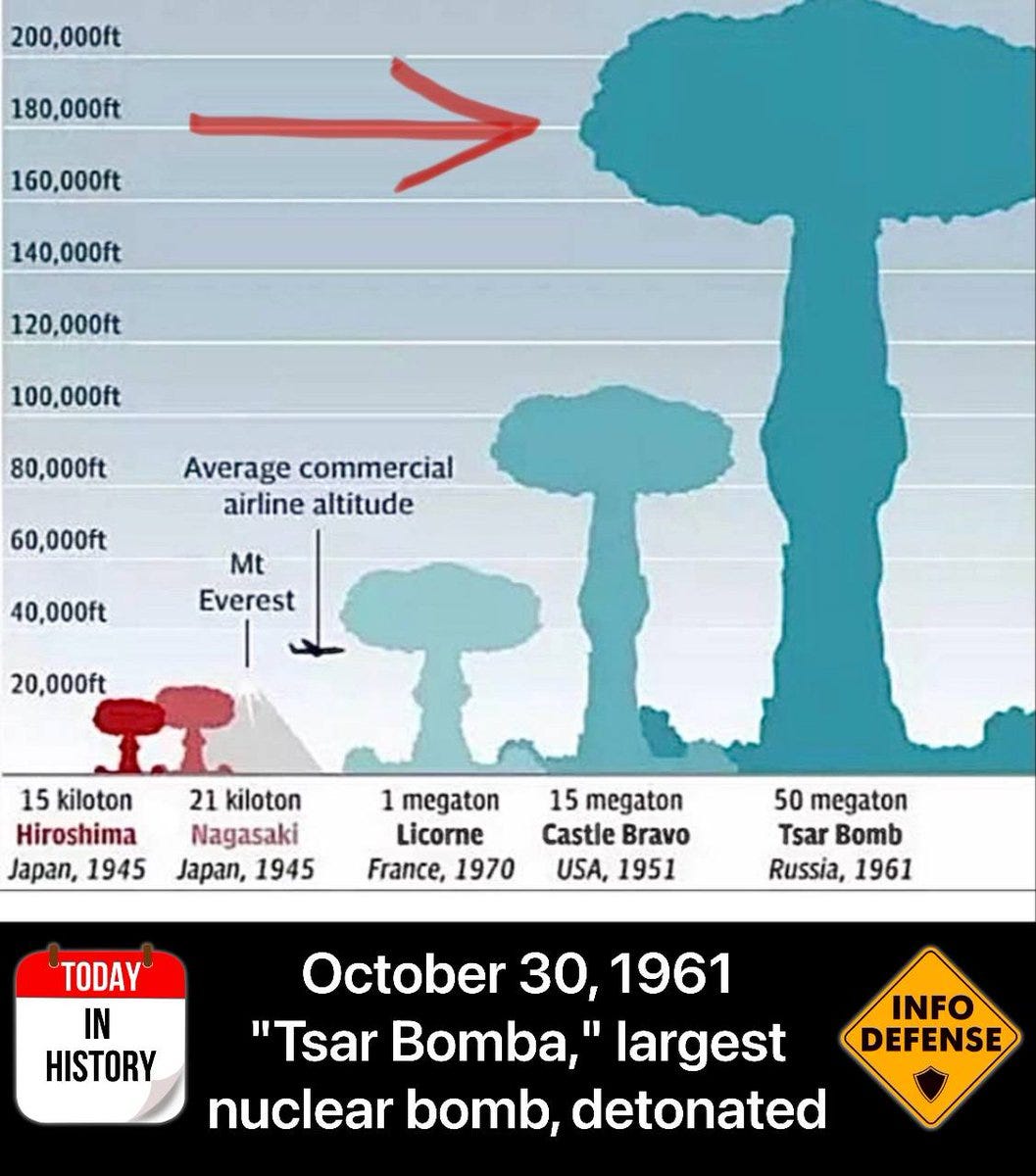

Shortly before lunchtime on October 30, 1961, a Soviet plane flying above the Arctic archipelago of Novaya Zemlya dropped the most powerful nuclear bomb ever created.

The USSR’s 50 megaton Czar Bomba — “the king of bombs” — was designed to shatter Cheyenne Mountain and the NORAD headquarters underneath it. It was 3,000 times more powerful than the U.S. atomic attack that killed 90,000 people in Hiroshima two decades earlier, more than 100 times the explosive force of the largest U.S. submarine based warheads today.

When it exploded, it unleashed a six-mile-wide fireball and a mushroom cloud that loomed more than 40 miles into the sky. And the Soviets were testing it at only half of its designed capacity, to limit fallout. It was capable of a 100 megaton blast.

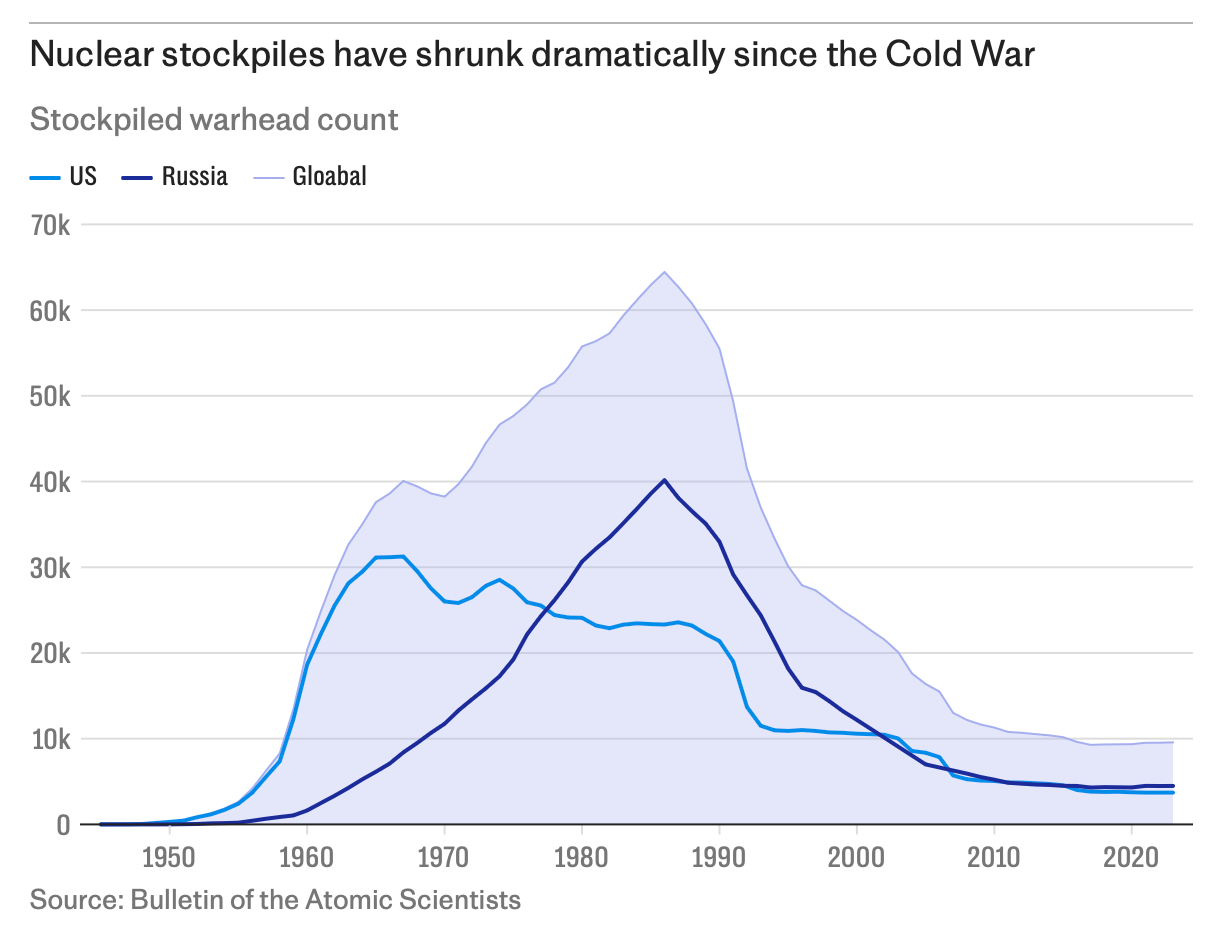

Since then, decades of negotiations and arms-control treaties have massively reduced American and Russian warhead arsenals, with neither side testing a nuclear bomb in more than three decades. The aim is straightforward: reduce the number of weapons sufficiently that even in an actual nuclear war, there are too few weapons to target more than a handful of each country’s cities, due to the much larger number of pressing military targets which would have to be destroyed. It’s also to add risk: if you can’t guarantee you’ll wipe out the enemy’s nuclear forces, you’ll think twice about an attack. Or so both sides hope.

But last week, the last of these bilateral agreements, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or “New START”, expired — and with it, hopes that the nuclear arms race had been consigned to the history books. It is the first time since the 1970s that the two powers have had no agreement in place without at least negotiations for a new treaty under way.

At a time of huge geopolitical upheaval, analysts and diplomats are concerned that the stage is set for a new nuclear arms race — one that could prove even more dangerous than the world has seen before. And for the first time in the history, the competition will not just be confined to Russia and the U.S.

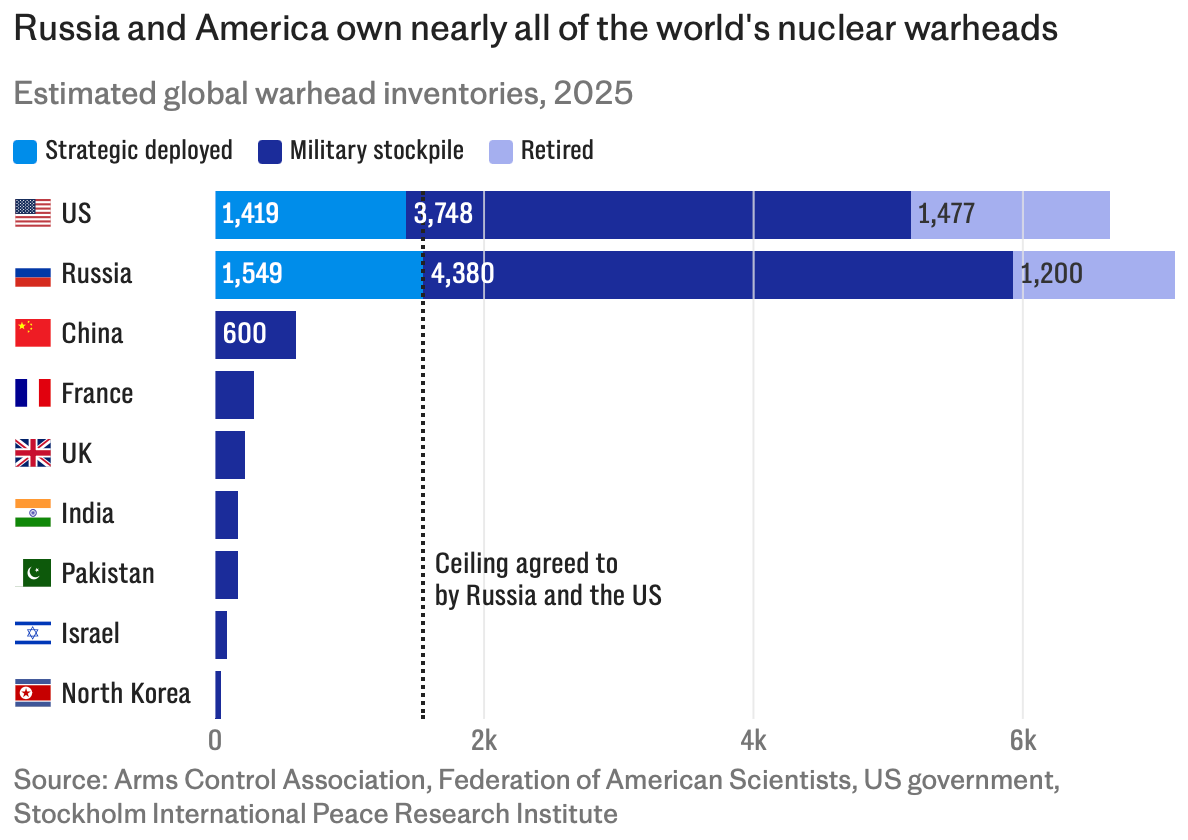

China has also been developing nukes at a startling trajectory, more than doubling its stockpile of warheads over the last six years.

And it is China’s rise that will be Donald Trump’s biggest concern.

A three-way race will be hugely destabilising for the world order. If America tries to build an arsenal large enough to deter its twin foes at once, it will spur an even more dramatic increase in their respective stockpiles.

“This is the end of an era. It is not the end of arms control but it is definitely the end of arms control as we know it,” says Heather Williams, director of the Project on Nuclear Issues at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Smaller nuclear powers such as Britain and France will also face pressure to bulk up. And there could easily be a proliferation of new nuclear states, whose own risk calculus may not match the powers that have shared the burden of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) for so many years.

Trump has insisted for decades that he wants denuclearisation. His Golden Dome missile shield aims to render nuclear weapons effectively obsolete. But whether it will, or whether it will soon enough, remain to be seen.

“Complete Collapse of Everything I Worked on for 45 Years”

Nikolai Sokov, who worked on Cold War nuclear arms treaties from the Russian side, says: “I was always quite proud of what I did. I negotiated agreements that resulted in about an 80 percent reduction of nuclear weapons.

“Now I see a complete collapse of everything that I worked on for 45 years.”

Cold War nuclear arms negotiations between the Soviet Union and the United States were intense and confrontational.

“They would say, ‘No, your proposal is completely unacceptable, it’s bull----’,” says Sokov, who was working for the USSR’s foreign ministry in the late 1980s, traveling between meetings at the U.S. and Soviet missions in Vienna several times per day.

Once, he and his U.S. counterparts spent 18 hours in non-stop negotiations over a draft text, haggling over the meaning of five individual words in the document.

“Food was brought to us at our table. He suffered because I smoke. Eventually we agreed on three words, and we had a reasonably good idea on how to finalise the remaining two,” says Sokov.

“Words mean something. They’re where heavy bombers are located, or how you look at warheads during inspections. It’s never just a word, it’s actual weapons.”

But these lines of communication and debate have now disappeared completely.

The New START agreement, signed by the then U.S. president Barack Obama and Russian president Dmitry Medvedev (Vladimir Putin was then prime minister) in 2010, was the last in the line of successive treaties that has reduced each power’s respective hoard of deployed warheads from 12,000 in the early 1990s to 1,550.

The deal capped all three nuclear weapon delivery systems: intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) and bombers. It also agreed rules around transparency, including the provision that each country would hold 18 on-site inspections of its nuclear weapons per year.

In 2023, Putin suspended Russia’s participation in the treaty, halting inspections and data exchanges. However, both sides have signalled they have kept within the numerical limits on the treaty. Currently, the U.S. has 1,419 deployed strategic warheads while Russia has 1,549.

In September, Putin said Russia was prepared to maintain the numerical limits of the treaty for one more year if the U.S. “acts in a similar spirit”. But in January, the Kremlin said it had still not received a response from President Trump.

“If it expires, it expires. We’ll do a better agreement,” the Trump told The New York Times last month. Trump called New START a "bad deal" that was being "grossly violated," and said the United States should instead pursue a "new, improved and modernized treaty."

But so far, there are no talks in the works.

“No one is even talking about negotiations, except for very general statements,” says Sokov, who is now a senior fellow at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation.

“The problem is we’re losing all kinds of predictability that we used to have.”

Yet Trump is right about Russian violations and general perfidy. Putin has repeatedly used nuclear threats (all bluffs so far) to pressure the West over its support for Ukraine. The Russian leader has placed nuclear weapons on heightened alert and announced that Russian nuclear weapons will be deployed in Belarus. He has also been investing heavily in new delivery systems, such as Russia’s Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missiles that can travel at 2.1 miles per second.

Without a nuclear disarmament treaty in place, the first thing that the U.S. and Russia are likely to do is rapidly increase the number of deployed warheads. Both countries have much larger stockpiles in reserve.

In the short term, simply by uploading more of its existing warheads onto its ICBMs, SLBMs and bombers, each side could double its strategically deployed warheads to somewhere around 3,000 each within a year or two, says Daryl Kimball, the executive director of the Arms Control Association.

Including “non-deployed and retired warheads” — those which cannot be launched at the touch of a button — the U.S. has 5,225 while Russia has 5,580. Combined, they hold 87 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons.

For now.