Criminalizing Conquest: 80 Years of the UN Charter’s Abolition of Wars of Aggression

The UN turns 80 today. Awful though it may be, its founding marked an astonishing global milestone: the abolition and widespread rejection of wars of conquest.

This essay is free, but with Premium Membership you get MORE. Join today.

by Rod D. Martin

June 26, 2025

Eighty years ago today, the leaders of the allied powers that won World War II met in San Francisco to sign one of the most consequential treaties in history: the Charter of the United Nations.

The UN itself, of course, has been a disaster: a cacophonic corrupt talking shop that accomplishes few of its stated aims while giving dictators a global stage. Who could have seen that coming? Clearly not FDR.

But the motivation of the participants, ravaged by a war that had nearly destroyed most of them and had threatened the world with subjugation and slavery, was sound. What Roosevelt and Churchill had dubbed “the United Nations” — the Allied powers in World War II — came together in San Francisco to form a more permanent institutional structure for their alliance, based on one simple hope: “never again.” To achieve that, they established a more robust successor to the League of Nations, they pledged to establish and maintain collective security, and most consequentially, they legally abolished wars of aggression and conquest.

Most of what they did eighty years ago failed. That last bit changed the world.

A World Transformed

For most of human history, conquest wasn’t just common — it was lawful. Most of the world belongs to one nation or another “by right of conquest”, a legitimate principle of international law prior to 1945. Kingdoms rose and fell by the sword, and no one questioned it. Borders were made not by consent but by blood.

Put another way, 2,000 years after Golgotha, in this enormously consequential area at least, international affairs operated on pagan, not Christian, principles. Might made right, the strong devoured the weak, and history celebrated the conquerors. Empire was glory. Subjugation was fate.

But then, quite suddenly in historical terms, the world changed.

Eighty years later it is difficult to overstate how thoroughly, quietly, and quickly the ancient assumption of conquest as legitimate has been utterly dismantled. Hitler was surely an evil man, but he was not alone in seeing no moral impediment to the forcible annexation of large parts of Europe: how was doing so any different from the conquest of India, or of the Aztecs, or of Gaul? By 1939 most civilized opinion had turned against this…notably excepting the conquests and colonial empires that already then existed. But a generation earlier, or ten, or a hundred, people might have opposed specific conquests but certainly not the right to conquer, much less the rights that conquest conferred.

Today, when one nation invades another to seize territory, the entire world recoils. Governments condemn it. Media flay it. Common people are aghast. Sanctions follow. This is exactly why Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has horrified so much of the world. Social media notwithstanding, it’s not any great pre-existing love for Ukraine, which few could have found on a map (and indeed, which few can find now). It’s that the world isn’t supposed to work this way anymore.

Countries just aren’t supposed to invade and conquer each other anymore, and not just countries we care about: any countries at all. It’s why the world mobilized behind America to kick Iraq out of Kuwait. Who cared about Kuwait? No one, not even their neighbors. That wasn’t the point. No one wanted to revert to the world of the before-time, in the long long ago.

That’s a sea change. An earthquake. An enormous reformation in human thought. Even the would-be conquerors dress up their plans and actions in rhetorical clothing that masks their true intent. They’re ashamed, just as they’re ashamed not to pretend they’re all “democracies”.

On this, the 80th anniversary of the UN’s founding, that point must be made. The UN itself is awful, if occasionally useful. But the abolition of wars of conquest is one of humanity’s greatest achievements. It should be noted and celebrated.

The UN Charter declared a new standard. It legally established the principle of self-determination and banished perhaps the most natural ambition of man. And in that, it’s mostly worked, as spectacularly as the UN itself has failed.

How Conquest Became Unthinkable

World War II was the deadliest conflict in history. Hitler wanted Lebensraum. Japan sought its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” Hitler carved up Eastern Europe with Stalin before turning on his co-conspirator.

The cost was absolute devastation, and death on a scale theretofore unknown. And not long after the UN Charter was signed, Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the world’s nations to confront the very real possibility that a third engagement might be the world’s last. Perhaps two world wars in a generation were enough.

But it’s easy to understand the attraction of conquest, especially if you believe (as humanity mostly has) that “might makes right”, and if you don’t think of those beyond the next hill as having rights, or at least any rights you can’t instantly redefine by glorious battle.

Conquest is as old as civilization itself. It is no accident that the first conqueror (at least in the postdiluvian world) was Nimrod, a great builder, yes, but also a dominator, an archetype of rebellion, and the first to unite men by force for the purpose of expansion. From Nimrod to Nebuchadnezzar, from Alexander to Attila, from Darius to Disraeli, every great empire expanded thus. Power was taken, not given. The map was drawn in red.

There was no shame in this. Quite the opposite — it was admired, well into modern times. Conquerors were lionized. Textbooks celebrated their exploits. Resistance was heroic, but conquest was legitimate, and glorious. Slavery, famine, forced migration, even genocide were not aberrations — they were tools of statecraft. They were not unbounded, especially in the Christian West. But they were ever-present nonetheless.

Indeed, the jus belli, the “right of war,” was universally accepted.

But 1945 marked a break.

Don’t miss this FREE 2nd excerpt from my new Essays on the Counterrevolution. You can also get the book itself for FREE when you become a Premium Member!

The death camps of Europe, the rape of Nanking, the horrors of the Russian Front, the firebombings of Rotterdam and Tokyo, and finally the mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki — these horrors forced a reckoning. It wasn’t so much that all of these things were seen to be immoral: indeed, the victors saw their acts as just, if horrifying, necessities to prevent a far greater evil. Rather, it was the pervasive shellshocked sense that the world could no longer afford conflicts which required such things at all.

Led by the United States, the world’s victors decided the old system must end.

And so the UN Charter boldly declared and enshrined into the laws of its signatories that member states would refrain from “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”

This is the cornerstone of what we today call the Rules-Based International Order.

It might not have stuck but for the atomic bomb. The UN certainly turned out to have no enforcement mechanism that was up to the task.

But once the world grasped that its continued existence was at stake, humanity adopted this abolition of wars of aggression as a core principle of morality. Overnight they came to believe that people not only ought but do have the right to decide for themselves who rules them, and not to be forced at sword- or tank-point into slavery by Baghdad, Belgrade, or Berlin.

That the Americans led in this was no accident. Self-determination was a founding principle of the American Revolution, which had also thrown off a distant colonial overlord. It came to be the rallying cry of colonies across Africa and Asia. And that right of self-determination, now enshrined in both international law and the collective consciousness, was not merely political. It was an expression of Jefferson’s idea of unalienable rights.

And to be unalienable, such rights must be granted by God, the same God Who commanded us to love our neighbors as ourselves.

It is no small irony that the secular leaders who formed the UN abolished the greatest remaining expression of paganism in favor of Christian principle, something the church had been unable to achieve for nearly 2,000 years.

Success in Spite of the UN

The UN was founded by the victorious allies, most of whom were not merely democracies but cradles of Western civilization. Those that weren’t were a distinct minority…in the beginning.

Over the next two decades that changed, an unfortunate byproduct of decolonization turning out to be the accession of countless dictatorships. The UN came to be dominated by nations opposed to the West — and Western civilization — in whole or in part. They routinely use the UN’s corrupted institutions to advance their human rights abuses while condemning the free nations. Even the UN’s “peacekeepers” have become a disgrace: aiding Hamas in Gaza, standing by during the Srebrenica massacre and the Rwandan genocide, committing mass rape in the Congo. The list goes on and on.

And yet in spite of all that, a new global norm emerged — not perfectly, not immediately, but powerfully: you do not take your neighbor’s land by force. It wasn’t just a law, or “a scrap of paper.” It became a taboo.

The question, of course, is “how”?

Several key forces drove the shift:

Nuclear Deterrence: The sheer horror of the Bomb made traditional great-power wars virtually unthinkable. The old calculus of conquest was replaced by existential risk.

American Hegemony: For the first time in history, a dominant superpower chose to stabilize rather than conquer. Even Britain had not achieved this. The U.S. protected the borders of allies, deterred aggression, and promoted sovereignty — not annexation.

Economic Interdependence: Globalization created prosperity through trade, not empire. War became a painful net loss.

Cultural Transformation: The world, increasingly shaped by Western ideals and the rapid spread of Christianity, began to see conquest not as heroic but as monstrous. Even totalitarian regimes gave lip service to human rights. Decolonization reshaped moral assumptions.

Mass Media and Civil Society: War was no longer hidden. Not just aggression but just war as well were broadcast in real-time and condemned by global audiences.

What emerged was a new civilizational standard: the sanctity of national borders. Holdouts remain, such as China and Russia, but the vast majority came to believe in government by the consent of the governed, from Nairobi to New Delhi to New York.

And the violators? North Vietnam conquered the South, yes, but only after pretending for decades that its subversion was “an indigenous uprising”. The Soviet Union acted similarly in Eastern Europe and the Third World, subjugating still-technically-independent countries while trumpeting their liberation (and thus acquiring their votes at the UN and other international bodies). Few are those who’ve baldly asserted the right of conquest: Iraq unsuccessfully, Russia partly so in Ukraine, China brazenly in Tibet (and perhaps someday Taiwan).

But the violations stand out because they are so rare — and so universally denounced.

You Can Thank America

As uncomfortable as this may be for globalists, the truth is undeniable. The reason for the peace is the Pax Americana. And if that ever went away, humanity’s newfound morality would disappear with it.

After 1945, the United States built a global system in which conquest was both unprofitable and punished. It built NATO, guaranteed Asian peace, and protected trade routes. It deterred the Soviets, restrained its own allies, and won the existential Cold War, without which victory conquest would have become the norm.

American power, not UN diplomacy, preserved the peace.

But America used that power to export an idea, in San Francisco 80 years ago and ever since: that nations have the right to be free and sovereign, and that empire belongs to the past. On this, FDR, Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, and Donald Trump stand agreed. Indeed it is that exact nationalism — that principle of self-determination — that ended the old empires, the ones that survived the war. It created the institutions and values that made aggression not just risky, but shameful.

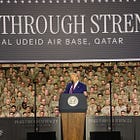

The lesson is plain: peace requires strength. And the peace we’re speaking of is not merely the absence of war, but the rejection of aggression — the delegitimization of empire.

The legal abolition of conquest is one of the greatest leaps in human history. For millennia, the strong ruled. Borders bled. Nations rose and fell under the heel of stronger men.

No longer.

So while we sadly cannot celebrate the 80th anniversary of the UN itself, we can and ought celebrate the vision of its framers — yes, even FDR — pregnant with hope for a better world and a better humanity. To a great degree they accomplished that dream. And we are all beneficiaries of their vision and their gift.

Wonderful writing supporting truths. TY, Rod.

Back in my long-lost youth, there was an anecdote that made the rounds, attributed to one of the early SecGens (I believe it was Dag Hammarskjold): "Here at the UN, everything disappears. If there's a conflict between two small countries, the conflict disappears. If there's a conflict between a large country and a small one, the small country disappears. And if there's a conflict between two large countries...the UN disappears!"

The UN has about as much to do with the "de-moralization" (for want of a better term, but certainly far more descriptive--even in your own terms!--than "criminalization") of war since 1945 as the League of Nations had between the wars, during which time most of the nations of the world signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact which was supposed to outlaw war for all time. How'd that work out?

And even if you assign some role to the UN, it is no more significant than any role that might have been played by the Concert of Europe--the 19th-century version of the UN or the League--in maintaining the so-called "Long Peace" between 1815 and 1914. The real result was that international conflict--including wars of conquest--were simply exported from Western Europe to other, less-developed parts of the world.

But let's get back to the UN. No wars of conquest? How about Israel's being the target of not one, not two, not three, but FOUR separate, coordinated, international attempts to eradicate it from the map? That would be 1948, 1956, 1967, and 1973 (I am old enough to have lived through the last of these as a teenager: at the time we all thought we were going to die in a nuclear exchange after it seemed the USSR might actively intervene on the side of its client state, Egypt).

And the UN's role in all that? Lots of speeches; meaningless resolutions (necessarily so: the USSR stood ready to veto anything actually meaningful); and--after the dust had settled--patrolling the battlefield and bayoneting the wounded.

Since I mention the USSR's pivotal role in preventing the UN from acting, let's talk about the conflict in which they figured that out: Korea. The ONLY reason the US was able to get UN backing for its defense of Korea from the North's aggression was that the Soviets--unaccountably--decided to boycott the Security Council, allowing the other four permanent members--the US, UK, France and the ROC--to prod the UN into "action."

Would the NORK attempt to "reunify" the Korean Peninsula count as a "war of conquest"? I certainly do: no less so than the North Vietnamese conquest of what was by 1975 a sovereign nation, the Republic of Vietnam. And what role did the UN play in Korea? As a fig-leaf for a US-led international coalition. That's all. The UN needed the US, not the other way around.

You said a couple of things that are in fact quite correct: the post-War "peace" was largely if not entirely underpinned by two factors: the Bomb, and the United States. Indeed it's the combination of the two, as I daresay if the post-War order had seen the USSR as sole owner of the Bomb rather than the US...let's say we'd likely not be having this discussion. But the UN role? Negligible at best, toxic at worst.

I normally find myself largely in agreement with you. But not today.