Does the President Have Legal Authority to Blow Up Venezuela's Drug Boats? Turns Out He Does.

Presidents can act legally and decisively against transnational threats like narco-terrorists under relevant statutes and Article II of the Constitution, no matter what the New York Times claims.

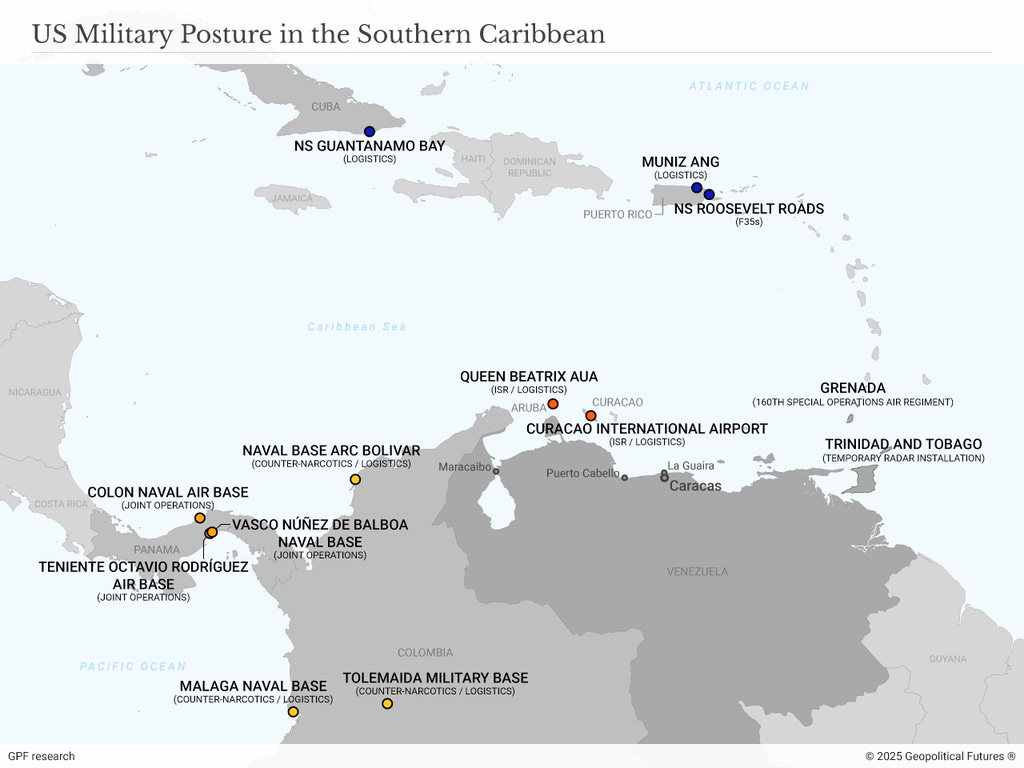

Don’t miss our Deep Dive on the U.S. military buildup off the coast of Venezuela.

Black Friday sale ENDING: 20% off plus TONS of bonuses! Upgrade by Midnight!

NOTE: In light of the New York Times’ bogus claims yesterday that the President’s attacks on Venezuelan drug shipments are illegal, it seems needful to provide you this briefing on the history and legalities, which we originally ran a month ago (we know you’ve slept since then).

This analysis was exclusively for Premium and Inner Circle Members when it first ran. Today, you can read it for FREE, as a sample of what you get when you upgrade.

I further note that during the twelve years that Barack Obama and Joe Biden fired 963 cruise missiles and ordered more than 692 drone strikes on individuals they had designated foreign terrorists (including some U.S. citizens), I do not recall the New York Times ever suggesting that Obama or Biden were war criminals. Not once. — RDM

by Clifford Angell Bates, Jr.

November 4, 2025

All the moaning about the president acting without Congress that I hear coming out of the mouths of Democrats, Libertarians, and so-called Conservatives alike just sets me off. Ah, the dangers of being bored away from one’s office and library, with idle hands, an hour to kill, and a tablet loaded with LexisNexis, constitutional law databases, and a speech-to-text editor that tempts mischief.

Voila — what began as an impatient reaction to partisan lamentations became a deeper inquiry into one of the oldest questions in American constitutionalism: when, and to what extent, may the president act without Congress?

The tension between legislative authority and executive initiative is as old as the Republic itself. It animates the framers’ careful division of powers in Articles I and II of the Constitution.

Still, it also exposes the dynamic, sometimes volatile, nature of American governance in times of crisis. From Jefferson’s naval expeditions against the Barbary pirates to modern operations against narco-terrorist cartels on the high seas, presidents have repeatedly asserted inherent or delegated powers to protect the nation and enforce federal law, often before or without explicit congressional authorization.

Critics decry these actions as executive overreach; defenders invoke constitutional necessity and historical precedent.

In this essay, I examine constitutional equilibrium through the lens of Article I, Section 8, Clause 10 — the Define and Punish Clause — and its interplay with Article II’s Take Care and Commander in Chief Clauses. It explores how Congress’s power to legislate against piracy, felonies on the high seas, and offenses against the law of nations has evolved into statutory regimes like the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act (MDLEA), and how these statutes, in turn, empower the president to interdict, seize, and, in extreme cases, use lethal force against narco-traffickers and narco-terrorists operating beyond U.S. territory.

The essay further examines the limits of this authority, including concerns about due process, the extraterritorial application of the Bill of Rights, and the scope of modern Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs).

Ultimately, the debate is not about executive tyranny but constitutional interpretation: whether the architecture of separated powers was designed to restrain decisive action or to enable it when the Republic’s security and laws are at stake. In an era of transnational criminal networks and asymmetric warfare, the old quarrel over presidential power is anything but academic — it defines the frontier between legality, necessity, and survival.

Hostis Humani Generis and Legal Foundations

The legal concept of hostis humani generis comes from United States v. Smith (18 U.S. 153, 1820). Pirates, the Court explained, are “enemies of all mankind.” This principle allows universal jurisdiction over pirates. Any nation may apprehend and punish them, regardless of nationality or location.

The framers incorporated this principle into the Define and Punish Clause. Borders do not limit felonies on the high seas. Congress can legislate broadly. The executive can enforce.

Modern narco-terrorists fit the same model. Cartels that traffic drugs with violence, coercion, and cross-border operations pose threats comparable to piracy. They endanger commerce, security, and human life globally. Like pirates, they act beyond any one nation’s control. Hostis humani generis provides a legal and historical justification for the president to act decisively, even in the absence of direct congressional authorization for each operation.

Drug trafficking qualifies as a high-seas felony because Congress defines it so. United States v. Smith distinguished traditional piracy from other maritime crimes. The principle remains: Congress may classify offenses that threaten international order.

Narco-terrorists who use violence violate the law of nations. Universal jurisdiction applies. Congress legislates. The executive enforces.

Congressional Action and Statutory Authority

Congress codified this authority in the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act of 1986 (46 U.S.C. §§ 70501–70507). The MDLEA criminalizes drug manufacture, distribution, and possession on vessels subject to U.S. jurisdiction on the high seas. Penalties include life imprisonment. Jurisdiction applies automatically to U.S.-flagged vessels, universally to stateless ships, and to foreign-flagged vessels with flag-state consent. Over thirty countries, including Colombia and Mexico, have agreements with the U.S. No direct U.S. nexus is required for stateless vessels.

The Coast Guard may board, search, and seize vessels and arrest suspects without warrants under 14 U.S.C. § 89. Courts have upheld these actions as consistent with the Constitution and statutory authority. United States v. Villamonte-Marquez (462 U.S. 579, 1983) confirmed that mobility and border-search exigencies justify warrantless boardings. United States v. Suerte (291 F.3d 366, 5th Cir. 2002) held that drug trafficking on the high seas falls within the scope of high-seas felonies. United States v. Bellaizac-Hurtado (700 F.3d 1245, 11th Cir. 2012) clarified that the law does not extend to territorial waters without the consent of the relevant nation. United States v. Ballestas (795 F.3d 138, D.C. Cir. 2015) upheld conspiracy liability for off-vessel actors as necessary and proper to enforce high-seas felony provisions.

The Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. § 952) complements the MDLEA by prohibiting the importation of controlled substances. Together, these statutes give the president apparent authority to act against international drug trafficking networks.

Executive Authority in Practice

The president’s authority derives from the Constitution and congressional statutes. Article II makes the president Commander in Chief. Section 3 mandates that the president “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” These clauses empower interdiction, seizure, arrest, and, in extreme circumstances, the use of lethal force.

Historical precedent supports decisive executive action. Revenue cutters in 1790 patrolled the high seas. In 1973, over a ton of marijuana was seized from the Big L (a 42-foot sport fisherman boat) in the Florida Straits. Today, interdictions cover six million square miles of ocean.

Deadly force is lawful under limited circumstances. Graham v. Connor (490 U.S. 386, 1989) establishes the standard of objective reasonableness. It applies when traffickers violently resist, threaten officers, or risk scuttling vessels. Coast Guard rules of engagement require proportionality. Executive Order 12333 prohibits assassination. MDLEA enforcement provides the legal authority to use lethal force when necessary and reasonable.

Narco-Terrorists and the AUMF

In January 2025, the Trump administration designated groups such as Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua as Foreign Terrorist Organizations. That allows operations to shift from law enforcement to counterterrorism. The president may act under Article II self-defense powers. Notification to Congress is given under the War Powers Resolution (50 U.S.C. §§ 1541–1548).

More importantly, these operations fall within the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). The AUMF permits force against those who planned, authorized, or aided terrorist attacks or harbored such organizations. Modern narco-terrorists who threaten U.S. security clearly fit this category. The president’s authority is inherent as Commander-in-Chief. Courts and the executive branch have repeatedly affirmed this power to repel attacks.

A classified Justice Department opinion in October 2025 explicitly authorized lethal strikes on cartel leaders and vessels. It framed narco-trafficking as an ongoing armed attack under international law. Article 51 of the UN Charter recognizes the right of the U.S. to self-defense in such circumstances. No territorial invasion or new congressional declaration is required. Proposed 2025 bills for cartel-specific AUMFs merely affirm preexisting delegations. They do not expand or constrain executive authority.

Recent operations, such as strikes on Caribbean speedboats and Venezuelan vessels, were legitimate exercises of delegated war powers. Legal analyses confirm that groups like Tren de Aragua align with entities covered under the AUMF. Notifications to Congress declare a formal armed conflict. This underscores the settled nature of executive authority in defense of national security.

Constitutional Limits and Due Process

Some critics invoke the Fifth Amendment to argue that foreign targets are entitled to the same due process protections as Americans. These arguments fail under Supreme Court precedent.

In United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez (494 U.S. 259, 1990), the Court held that the Bill of Rights does not automatically apply to non-citizens outside the United States. Thus, rights hinge on citizenship and sovereignty, not mere exposure to U.S. law enforcement.

Similarly, Boumediene v. Bush (553 U.S. 723, 2008) confirmed that habeas corpus rights extend only when the United States exercises de facto sovereignty over the individual. On the high seas, these limits make clear that foreign nationals cannot demand full constitutional protections when intercepted in transnational operations.

High-seas law enforcement and military exigencies further justify limited constitutional application. Mobility of vessels, armed resistance, and the transnational nature of narco-trafficking make standard procedural safeguards impractical. Courts have recognized this operational reality. United States v. Bellaizac-Hurtado (700 F.3d 1245, 11th Cir. 2012) affirmed that courts can limit domestic overreach but generally defer to executive decisions abroad, especially when Congress has delegated authority through statutes like the MDLEA. This balance ensures lawful enforcement while respecting constitutional boundaries at home.

International criticisms, including UN expert reports, have raised human rights concerns over lethal actions against traffickers. While morally persuasive for some, these critiques carry no legal authority over the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that constitutional primacy governs U.S. actions. The executive may enforce the law abroad to protect Americans from imminent threats to their safety. Narcotics flows and cartel violence pose clear and immediate dangers, justifying decisive intervention under both statutory and constitutional authority.

Historical precedent reinforces this understanding. From the Barbary Wars to modern counter-narcotics operations, presidents have acted abroad to suppress piracy and criminal networks without invoking domestic procedural protections. Modern narco-terrorists on the high seas are the functional equivalents of 18th-century pirates, hostis humani generis. Universal jurisdiction and practical necessity allow the executive to act decisively. Constitutional limits apply primarily within U.S. territory, leaving the president free to protect American lives and enforce federal law against transnational threats.

Conclusion

Clause 10 of Article I gives Congress the power to define and punish piracy and felonies on the high seas. Statutes like the MDLEA implement that authority. The president enforces those laws under Article II of the Constitution. This includes interdiction, seizure, arrest, and lethal force when necessary. Narco-terrorists fall under the same framework, reinforced by the 2001 AUMF. Executive action is lawful, constitutional, and historically grounded.

The Founders intended decisive executive action when the nation’s laws and security are threatened. Hostis humani generis principles justify universal jurisdiction over high-seas threats, whether pirates of the 18th century or modern narco-terrorists. Courts, statutes, and precedent all support robust executive authority. Critics who call these actions overreach misunderstand the Constitution. In an era of transnational criminal networks and asymmetric threats, the old quarrel over presidential power is no academic exercise. It defines the line between legality, necessity, and survival.

The Trump administration’s actions on the high seas in 2025 enforce law, protect commerce, and safeguard lives. They are lawful, justified, and necessary. The Constitution provides the authority. History and precedent validate its use. Executive power, exercised decisively, fulfills its intended constitutional role.

Black Friday sale ENDING: 20% off plus TONS of bonuses! Upgrade by Midnight!

Absolutely the President has the legal authority to strike these Venezuelan boats full of drugs and Narcoterrorists and he should! These men are dangerous criminals who are dealing poison to men, women and children all across the America! No, they are not innocent civilians as their families claim. That’s just to cover-up what they were really up too. President Trump has acted decisively to fight them and take them out. Under international law he has every right to as they are basically pirates. Under the AUMF he has the authority to do so as drug cartels are rightly classified as terrorists. The Constitution, last but not least gives the President the authority to act under two articles of the Constitution. Obama and Biden did hundreds of unilateral strikes on foreign enemies and terrorists including U.S. citizens and no one said a word. Why are they all of a sudden against such strikes when Trump does it?

These Cartels you have to understand, aren’t just some rinky dink street gang, they’re like an army in of themselves and have more employees than some of this biggest corporations on Earth. They have tanks, armored cars, helicopters, assault weapons, bullet proof vests, and body armor. Military strikes are the only way to deal with heavily armed narcoterrorists trafficking drugs to kids, teens, mentally ill people, poor people, minorities, homeless people, veterans, and addicts all of whom are particularly vulnerable to their pushers. Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro is making billions every year off all these drugs and building up his narco empire. He’s like Pablo Escobar if he were a dictator of a nation. Trump is taking it to these narco kingdoms which rule over and terrorize all of Latin America.

But it's not nice to kill narco terrorists who are smuggling drugs to the US! It's MEAN. We should just give them Social Security Numbers and register them to vote. That'll fix the problem.