The Geopolitics of the Lewis & Clark Expedition

The intrepid explorers set out on this date, more than two centuries ago. Few moderns appreciate the magnitude of that endeavor.

This article is free, but with Premium Membership you get MORE, including a FREE copy of my new book, Essays on the Counterrevolution. Join today.

by Rod D. Martin

May 14, 2025

Today marks the anniversary of President Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery, better known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which left St. Louis on this date, May 14, 1804.

Few moderns appreciate the magnitude of that endeavor.

It is difficult to fathom the world of that day. For the first time in history, global population had just reached one billion souls, yet barely five and a half million lived in the seventeen United States. Of those, the vast majority still clustered along the Eastern Seaboard. West of the Appalachians, a relative trickle of pioneers had settled in the three states admitted to the Union beyond that ancient barrier: Kentucky, Tennessee, and — only a year earlier — Ohio.

The vast majority of the American frontier, even east of the Mississippi, remained wilderness. Civilization’s outposts were sparse and tenuous. The period of migration over the Wilderness Road through Martin’s Station at the Cumberland Gap was still in full swing. By 1810, some 300,000 settlers would pass through its gates — a staggering number by the standards of the day, and a testament to the determination of the American people to carve a new civilization out of the unknown.

Yet what lay beyond the Mississippi River — the Louisiana Territory, newly purchased from France — was terra incognita. It had no roads, no towns, no forts, no supply lines, no telegraphs, no steamboats, not even a map. To call it wilderness is almost to understate the case. Save for a few fur traders and trappers, it might as well have been another planet.

In many respects, an expedition to Mars today would be a lesser undertaking.

And yet, that is precisely what Jefferson intended to explore — and to claim.

The Louisiana Purchase, finalized just months earlier in 1803, had doubled the size of the United States overnight. But neither buyer nor seller had more than the vaguest understanding of what had been bought. There were estimates, guesses, and wild hopes, but no certainty, no surveys, and no practical understanding of the terrain, the peoples, or the prospects. Indeed, there was not even clarity on the Purchase’s western boundary. The French had hardly exercised sovereign control over the interior, and Spain still claimed adjacent territories with disputed borders. Russia was beginning to nose down the Pacific Coast. And Britain — embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars but still stinging from its recent expulsion from its thirteen American colonies — was watching all of it with interest from their fortresses in Canada.

The Geopolitics of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

In this climate, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was not merely a scientific mission, nor even just a bold act of exploration. It was the execution of a foundational geopolitical strategy — an urgent necessity for the survival and expansion of the United States.

The core of that strategy was dictated not by ideology, but by geography.

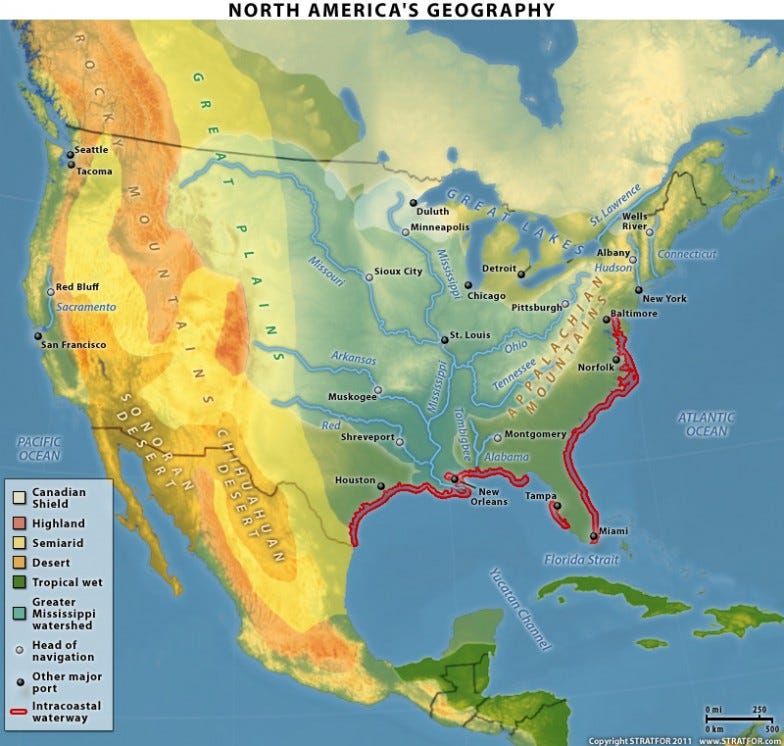

The American heartland — bounded by the Appalachians to the east, the Rockies to the west, and the Gulf to the south — is one of the most fertile and navigable regions on Earth. Its river systems, particularly the Mississippi and its vast tributaries — the Ohio, the Missouri, the Arkansas — form an internal highway system unrivaled anywhere in the world.

These rivers are not merely convenient: they are the lifeblood of American power. They connect thousands of miles of productive farmland and growing population centers to one another and to the sea. Barge transport being as much as three times cheaper than rail today, as much as an order of magnitude cheaper in 1850, and the only game in town in 1804, they thereby render the cost of capital formation vastly lower for America than for any other part of the world. They therefore compose one of the principal reasons for America’s staggering growth in the 19th Century, and why despite having just 4% of global population the United States today generates 26% of the world’s economy.

Economically as well as militarily, whoever controls the Mississippi River system controls North America.

In the early 1800s, that control was tenuous at best. American settlers had begun pouring into Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio, shipping their goods downstream toward market. But they did so at the mercy of foreign powers. The French, and then the Spanish, controlled New Orleans — the strategic chokepoint where all riverborne commerce exited to the world. If a foreign governor chose to close that port, as Spain had done in 1798, the entire western economy would grind to a halt. And as settlement increased, so would the magnitude of the problem.

That situation was intolerable. It threatened to fracture the nation along the Appalachian divide, splitting the Atlantic states from their western cousins, leaving the interior vulnerable to foreign subversion or seduction. It is no coincidence that the first secessionist movements in American history — Aaron Burr’s schemes, the intrigues of Wilkinson, Blennerhassett, and others — centered on precisely this geographic vulnerability.

New Orleans was thus not merely a trading post. It was the linchpin of national unity and survival. Jefferson understood this with crystalline clarity. The Louisiana Purchase was not about ideology or even expansion for its own sake. It was about securing America’s central artery — removing the knife from its throat. The rest of the Louisiana Territory was a buffer, a glacis, a shield around the core. Pre-settlement, the purchase wasn’t about the frontier: it was about the center.

Did Jefferson imagine settlement? Certainly: the essence of “Jeffersonian democracy” was the creation of a nation of small freeholders, people who controlled their future by owning small businesses — farms. But through the middle of the century, the territory of the Purchase was called “the Great American Desert” for a reason. It took Lincoln’s twin achievements of the Transcontinental Railroad and the Homestead Act to make the Great Plains habitable for non-nomadic civilization.

So territory on paper is not territory in fact. The land had to be mapped, claimed, and integrated. At the very least, that would take time. The presence of rival powers — Britain in Canada, Spain in Texas and the Southwest, Russian interests probing from the north, and restless indigenous tribes throughout — made that imperative urgent. If America did not extend its reach, someone else would, no matter who had purchased what.

This made the Lewis and Clark Expedition vital.

They were not simply scouts or scientists. They were the vanguard of a continental assertion. By navigating the Missouri to its headwaters, by crossing the Rockies and reaching the Pacific via the Columbia River, they drew a line — implicit but unmistakable — from St. Louis to the Pacific. That line was not just a route. It was a corridor of sovereignty. It was a claim to the interior and to its exit. And it was a message to European powers: this continent belongs to a new kind of nation.

That corridor also had internal implications. Once the United States controlled the entire Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio basin, it could knit its interior together into a coherent whole — militarily, economically, and politically. No internal division could thrive if the rivers tied New York to St. Louis to New Orleans. No blockade could succeed if American goods could flow freely to market. No foreign coalition could break the country in two without first severing a river system hundreds of miles inland.

This is what America achieved through the Purchase, and what Lewis and Clark helped secure: a unified economic core, buffered on all sides, anchored by a single port, and connected by rivers that needed no maintenance and ignored the seasons.

The visionary Jefferson perceived the logic. Lewis and Clark began its implementation.

The Corps of Discovery

Jefferson’s instructions to the leader of the expedition were broad and ambitious: chart the terrain and the rivers, identify plant and animal species, establish peaceful relations and trade with the native tribes, collect geographic and ethnographic data, and — most importantly — stake a claim for the United States all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition was a scientific venture, yes — but it was also a political one, and emphatically a military one.

For this, Jefferson needed a man of particular gifts. He found him in Meriwether Lewis.

Lewis, a younger neighbor of both Joseph Martin and Thomas Jefferson in Albemarle County, Virginia, was in many ways born for this moment. Like Martin, Lewis spent considerable time among the Cherokee, gaining both cultural understanding and survival skills that would later prove invaluable. He graduated from Liberty Hall (now Washington and Lee University) in 1794 and quickly joined the Virginia Militia (over which Martin was still a commissioned General). He helped put down the Whiskey Rebellion and soon joined the small, professional U.S. Army, rising to the rank of Captain. In 1801, he left active duty to become Jefferson’s private secretary — a role that gave him both daily proximity to the President and interaction with the intellectual and political elite of the young republic.

He was just 30 when Jefferson chose him to command the most ambitious exploration in American history.

Lewis in turn selected William Clark, younger brother of George Rogers Clark, as his co-commander — a gesture that spoke volumes about his character and judgment. Clark was technically subordinate, yet in every meaningful way they shared the leadership of the Corps of Discovery. The two men were opposites in many respects — Lewis cerebral and introspective, Clark pragmatic and steady — but their partnership was seamless. Each filled in what the other lacked.

Their mission was as complex as it was dangerous. They were to travel up the Missouri River to its headwaters, then find a route to the Pacific Ocean, ideally by water. They were to document every plant, animal, mineral, and native language they encountered. They were to maintain a detailed record of longitude and latitude to produce accurate maps. They were to establish trade and relations with the native tribes. And beyond the Louisiana Territory, they were to claim the Pacific Northwest and Oregon Country for the United States before European rivals could do so. It was a complex and difficult agenda, with significant geopolitical implications Jefferson well understood might determine the fragile Republic’s future.

They were fewer than fifty men at the outset. Their equipment was primitive. Their path was unknown. They were utterly on their own.

And yet they succeeded.

The expedition took two and a half years. It spanned more than 8,000 miles, across the Great Plains, through the Rockies, down rivers, and into lands no American had seen. They suffered disease, injury, hunger, and near-constant peril. They built forts where none existed. They endured brutally cold winters with the Mandan and traversed nearly impassable mountains with the aid of the Shoshone and their young guide Sacagawea. They fought only one violent engagement — against the Blackfeet — but walked a razor’s edge between peace and death nearly every day. The fact that they lost only one man — Sergeant Charles Floyd, likely to appendicitis — is itself astonishing.

In the end, they succeeded in their mission, established relations with more than two dozen indigenous tribes, and reached the mighty Pacific itself. And then they returned, reaching civilization in September 1806, the entire mission completed on foot and by canoe in just two and a half years. The impact of their journey would take years to sink in. Their maps redrew the American imagination. Their journals — meticulously kept — provided a scientific and cultural archive that shaped the study of North American biology, anthropology, and geology for generations.

What began as Jefferson’s bold vision had become, by their return, a national certainty: that the United States was manifestly destined to span the continent, from sea to shining sea.

Jefferson appointed Lewis Governor of the new Louisiana Territory. He governed from St. Louis, still at the edge of civilization, wrestling with the intractable problems of administering a vast unsettled and lawless domain. He struggled with debt, political opposition, and what we would now recognize as depression. Just three years after his return, he died, most likely by suicide, at the age of 35.

Jefferson was heartbroken. He called Lewis “a luminous and discriminating intellect” and a man “of courage undaunted.” His loss was incalculable.

Clark, by contrast, lived into old age. For many years after Lewis’s death he served as Governor of the Missouri Territory (the entire Louisiana Purchase save the new state of Louisiana), and later as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, where he continued to shape U.S. policy on the frontier. He was a stabilizing force — quiet, respected, and deeply trusted by the tribes, negotiating 37, or one-tenth, of all ratified treaties between American Indians and the United States. When he died in 1838, he was buried with honors befitting one of the Republic’s greatest explorers.

Together, these two men — and their Corps of Discovery — left behind an enduring legacy: not only in their scientific observations, their charts and journals, or their geopolitical achievements, but in the spirit of the Republic they helped extend. Their journey was a testament to the idea that free men, guided by reason and faith, could undertake the impossible, endure the unendurable, and return triumphant.

Together they left behind an incalculable contribution to science, to exploration, and to the advance of the American Republic. Their expedition was not merely an adventure but an assertion: that America would not be a coastal power clinging to the ocean’s edge, but a continental one, willing to push into the unknown, to master it, and to make it a civilization and a home.

And on this anniversary of their intrepid journey, they are worthy of our honor and remembrance.

I loved reading Ambrose’s slightly plagiarized story of the journey. Now, I live next to Lewis & Clark College and Law School.

Nice. Thanks.