China's Great Leap Backward: So Much For the Next Dominant Superpower

The Chinese century is over. Facing upside-down demographic and economic trends, China is heading off the cliff. Trump's tariffs make that much, much worse.

Don’t miss our Deep Dive “The Illusion of Chinese Strength: Power, Paranoia, and the Temptation of War”. It’s one of the most important things we’ve ever published.

by Joe Tauke

May 22, 2025

The "Chinese century" is over.

After all the prognostications, projections and proclamations of the past 20 years asserting that China would soon overtake the U.S. as the world's dominant superpower, the People's Republic is now facing twin perpetual headwinds, and has no realistic options for countering either of them.

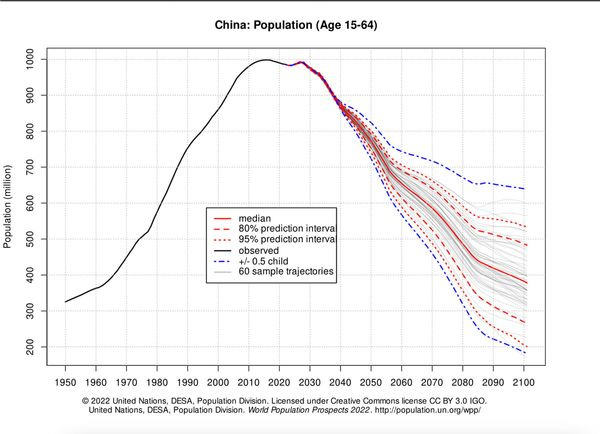

The first could accurately be described as the strongest long-term force driving the fates of all great powers: demographics. What was, for many previous decades,China's ultimate advantage — its never-ending supply of working-age laborers — peaked at almost exactly one billion people in 2010, according to the Chinese census. The next census, in 2020, revealed that for the first time since China's economic liberalization in the 1970s, the working-age cohort had shrunk, decreasing by more than 30 million.

Every age-related trend in China is going in the wrong direction. The nation's median age, once well below the Western world's, is now older than America's and headed further north with every passing year. Deaths outnumbered births in 2022 for the first time since 1961 and have continued apace. The fertility rate, which normally must be at 2.1 children per adult woman just to maintain a steady population, has slipped to below 1.1 — a figure made worse by the fact that, unlike in virtually every other country on the planet, China doesn't have a relatively even gender split in its adult population, the long-term result of male favoritism combined with the central government's infamous one-child policy. Basic math dictates that tens of millions of these "extra" men will never start families of their own.

To compound the problem even further, women in China have indicated lower interest in having children than ever before; more than two-thirds have expressed "low birth desire." According to Prof. James Liang of Peking University, fertility rates in Beijing and Shanghai have fallen to an astonishing 0.7, "the lowest in the world."

In Japan, economic stagnation produced a period that was called the "Lost Decade." That stagnation eventually persisted so long that some began to refer to it as the "Lost Generation." In China, an even more ominous buzz-phrase has become popular online: The "Last Generation."